Photograph: Ashwini Chaudhary/Unsplash

Greater organisational agility comes from empowered teams that perform well in solving the challenges that really matter to the business. But those teams don’t need to be big. Small, multidisciplinary teams empowered by digital technologies can generate a disproportionate amount of change and value in transformation programmes and beyond.

There is a temptation in large businesses to throw resources at problems, assuming that more brains and bodies mean better solutions. Internal politics result in people being included in processes who don’t really need to be there and don’t contribute much value. Representatives of functions that may only be needed at critical points get included in the project team from the beginning and have to attend every update meeting. The result is 20+ people sat in a room trying to move a project forwards. Everything slows down.

The reality is that more is not better for team effectiveness.”

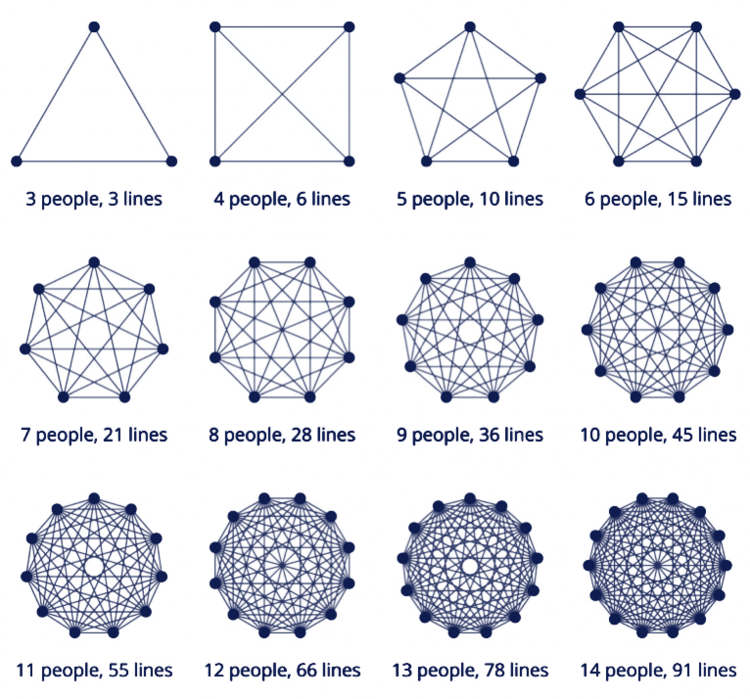

The reality is that more is not better for team effectiveness. Harvard professor (and specialist in team dynamics) Richard Hackman has shown that one of the key challenges with large teams is the growing burden of communication. Put simply, as group size increases, the number of unique links between people also increases, but exponentially.

Communication in teams is subject to a combinatorial explosion. In other words, as people are added to the team, the lines of communication are subject to a rapidly accelerating increase. Communication overhead increases dramatically, which very quickly comes at the expense of productivity.

Innovation flourishes in small teams

Small teams have other benefits beyond the ability to align, iterate and move fast. They are also more likely to generate new ideas. An analysis of more than 65 million papers, patents and software projects from science and technology found that whilst larger teams more often develop and consolidate existing knowledge, small teams are far more likely to introduce new and breakout ideas.

James Evans, one of the authors of the study and a Professor of Sociology and Director of the Knowledge Lab at the University of Chicago, described how larger teams tend to build on recent successes: “Big teams are almost always more conservative. The work they produce is like blockbuster sequels; very reactive and low-risk.”

Small teams, on the other hand, are more likely to come up with disruptive and innovative research and ideas, and appreciate the potential of the work they are doing.

Hackman defined four key features that are critical to creating an effective team in an organisation:

Common team tasks that work towards fulfilling a compelling vision

Clear boundaries in terms of who is in the team, information flow, and alignment with other resources, priorities, policies and teams

Autonomy to work within these boundaries

Stability

It’s therefore critical that we understand the difference between a real team and a looser “coacting” group and how a (surprisingly common) lack of clarity, direction and autonomy impairs the ability to move fast.

Big players know the value of small teams

Jeff Bezos, focused on retaining agility as Amazon scales, has famously described how teams in the company should get no larger than the number of people it takes to feed with two large pizzas (6–8 people). An effective small-multidisciplinary team is comprised of the people and skills areas needed to achieve key outcomes and no more.

Assembling smaller teams is important because it avoids not only communication problems, but also team scaling fallacy (the tendency for people to overestimate team capability and underestimate task completion time as team size grows) and relational loss (the feeling that it is difficult to get support in large teams).

The multi-disciplinary composition of the team is essential to achieving outputs and encouraging diversity. As Richard Hackman points out, homogeneity of team membership can often be a real problem in project teams since we tend to pick like-minded people to work with. Yet performance and creativity improve with greater diversity, including cognitive diversity and having a substantive range in views about how the work should be structured and executed: “It is task-related conflict, not interpersonal harmony, that spurs team excellence.”

The multi-disciplinary composition of the team is essential to achieving outputs and encouraging diversity. We tend to pick like-minded people to work with. Yet performance and creativity improves with greater diversity – including cognitive diversity.

One recent example of how small teams can empower greater agility is how Haier, one of the largest consumer electronics businesses in the world, was able to respond to the Covid-19 pandemic. Haier has a workforce of tens of thousands of employees who are organised into more than 4,000 microenterprises (MEs), many of which have only 10-15 employees. These MEs act as a network of small companies within the larger company, each with their own profit and loss account. They focus on specific business and customer groups and needs, with a high level of flexibility to adapt as required without lengthy, bureaucratic sign-off.

This flat and nimble organisational design enables the company to respond quickly to rapidly changing contexts. After the Covid outbreak in January 2020, Haier was able to fulfil 99.8% of orders throughout February and return to full capacity by the end of that month.

…

Digital technologies have transformed the dynamics of team contribution. Small, empowered teams can originate transformational ideas and successfully apply their capability to build and execute those ideas well. It’s time we reimagined how we resource value creation in business.